Operating system is in charge of making sure the system operates correctly and efficiently in an easy-to-use manner. The primary way the OS does this is through a general technique that we call virtualization. That is, the OS takes a physical resource (such as the processor, or memory, or a disk) and transform it into a more general, powerful, and easy-to-use virtual form of itself.

Turning a single CPU (or a small set of them) into a seemingly infinite number of CPUs and thus allowing many programs to seemingly run at once is what we call virtualizing the CPU.

Process

Process is the running program. The program itself is a lifeless thing: it just sits there on the disk, a bunch of instructions (and maybe some static data), waiting to spring into action.

Time-sharing is a basic technique used by an OS to share a resource. By allowing the resource to be used for a little while by one entity, and then a little while by another, and so forth, the resource in question (e.g., the CPU, or a network link) can be shared by many. The counterpart of time-sharing is space sharing, where a resource is divided (in space) among those who wish to use it. For example, disk space is naturally a space-shared resource; once a block is assigned to a file, it is normally not assigned to another file until the user deletes the original file.

Registers

The Program Counter (PC) (sometimes called the instruction pointer (IP)) tells us which instruction of the program will execute next; similarly a stack pointer and associated frame pointer are used to manage the stack for function parameters, local variables, and return addresses.

Process Creation

In early (or simple) operating systems, the loading process is done eagerly, i.e., all at once before running the program; modern OSes perform the process lazily, i.e., by loading pieces of code or data only as there are needed during program execution. Once the code and static data are loaded into memory, there are a few other things the OS needs to do before running the process.

Some memory must be allocated for the program’s run-time stack (or just stack). C programs use the stack for local variables, function parameters, and return addresses; the OS allocates this memory and gives it to the process.

The OS may also allocate some memory for the program’s heap. In C

programs, the heap is used for explicitly requested dynamically-allocated data;

programs request such space by calling malloc() and free it explicitly by calling free().

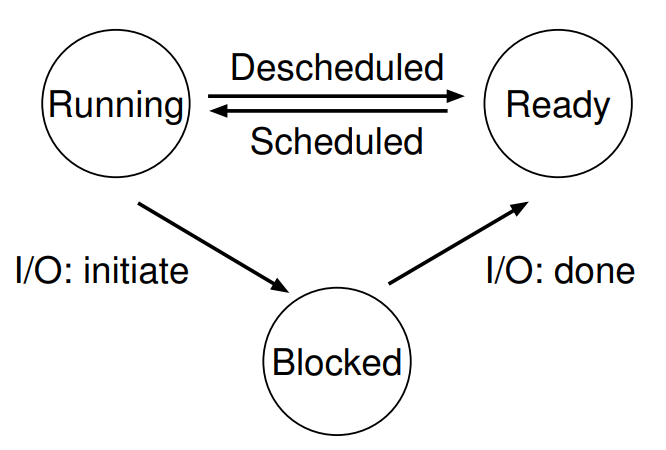

Process States

In a simplified view, a process can be in one of three states:

- Running: In the running state, a process is running on a processor. This means it is executing instructions.

- Ready: In the ready state, a process is ready to run but for some reason the OS has chosen not to run it at this given time.

- Blocked: In the blocked state, a process has performed some kind of operation that makes it not ready to run until some other event takes place. A common example: when a process initiates an I/O request to a disk, it becomes blocked and thus some other process can use the processor.

Data structures

The process list (also called the task list) to keep track of all the running programs in the system. Process Control Block (PCB) is the individual structure that stores information about a process, a fancy way of talking about a C structure that contains information about each process (also called a process descriptor).

APIs

These APIs, in some form, are available on any modern operating system.

-

Create

-

Destroy

-

Wait

-

Miscellaneous Control

-

Status

-

The

fork()system call is used to create a new process. -

The

wait()system call is used by a parent to wait for a child process to finish what it has been doing. -

The

exec()system call is useful when you want to run a program that is different from the calling program. -

The

pipe()system call is used to implement UNIX pipes. In this case, the output of one process is connected to an in-kernel pipe, and the input of another process is connected to that same pipe. -

The

kill()system call is used to send signals to a process, including directives to pause, die, and other imperatives.

Note

In the most UNIX shells, certain keystroke combinations are configured to deliver specific signal to the currently running process; for example,

control-csends aSIGINT(interrupt) to the process (normally terminating it) andcontrol-zsends aSIGTSTP(stop) signal thus pausing the process in mid-execution.

Note

The separation of

fork()andexec()is essential in building a UNIX shell, because it lets the shell run code after the call tofork()but before the call toexec(); this code can alter the environment of the about-to-run program, and thus enables a variety of interesting features to be readily built.

Signals

The entire signals’ subsystem provides a rich infrastructure to deliver external events to processes, including ways to receive and process those signals within individual process, and ways to send signals to individual processes as well as entire process groups.

Limited Direct Execution

In order to virtualize the CPU, the operating system needs to somehow share the physical CPU among many jobs running seemingly at the same time. The basic idea is simple: run one process for a little while, then run another one, and so forth. By time-sharing the CPU in this manner, virtualization is achieved.

- Performance

- Control

The hardware assists the OS by providing different modes of execution. In user mode, applications do not have full access to the full resources of the machine. In kernel mode, the OS has access to the full resources of the machine. Special instructions to trap into the kernel and return-from-trap back to user-mode programs are also provided, as well as instructions that allow the OS to tell the hardware where the trap table resides in memory.

Policy and Mechanism

Separate high-level policies from low-level mechanisms. Policies answer Which questions and mechanisms answer How questions.